Forum for discussion and essays on a wide range of subjects including technology, politics, economics, philosophy, and partying.

Search This Blog

Thursday, December 29, 2005

My Dad's Digital Watch

According to a NY Times article, "the average price of notebook[ computer]s sold at major retail stores in November fell to $980." This led Orrin Judd to title his excerpt of that article "The Kids Got Them in Their Happy Meals Yesterday", implying that notebook computers are getting so cheap, so fast, that soon they will be given away as little trinkets that kids get at family restaurants with their meals. It's easy to discount that as an Orrin exaggeration regarding deflation (one of his favorite topics), and while I doubt that actual notebook computers will every be included as part of a kids meal, Orrin may be more right than even he imagines.

Yesterday, at Rubio's (a small, southern California Mexican restaurant chain), the little trinkets in my daughters' kid's meals were digital watches. To be sure, these watches were not packaged anywhere nearly as nicely as my dad's watch, but the display and functionality surpassed that of my dad's.

In the course of 30 years, a gadget went from being a high end luxury item to being so cheap that it's a give-away trinket in a kid's meal. One day, in roughly 30 years, there will be a trinket with the equivalent technological complexity of today's notebook computers that comes with a happy meal. And no one will think twice about it.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year

But I do hope that everybody had a very Merry Christmas. I know I did. I'm not Christian, but this non-Christian really enjoys Christmas. What's not to like? I like the smell of the tree we buy every year. I like the festive lights. I like buying gifts for the kids. I like getting together with friends for a Christmas dinner. And I see that some of the rest of the non-Christian world is catching on.

I also noticed that this year was the first time since the 1950s that Christmas and the first day of Chanukah fell on the same day. From my perspective (as one with Jewish ancestry and descendents), this particular occurrence of that coincidence, in the United States at least, may be the first time ever where the Jewish population is not only tolerated by the greater society in which they exist, but are also welcome and accepted. Perhaps not quite universally welcome and accepted, but the Jews have never had a better home than the United States.

Friday, December 23, 2005

See what I mean

First, federal tax receipts have undergone a more than complete recovery from their plunge between 2000 and 2003 -- not "a partial recovery." According to the US Treasury's latest monthly statistical report, November tax receipts were $138.4 billion. Add that to the previous 11 months, and you get a trailing 12-month total for tax receipts of $2.171 trillion. That's the largest amount ever collected in a 12-month period. In fact, we've been setting records every month since August, when we first surpassed the $2.105 trillion record set in April, 2001.

Second, it's probably not true that "Revenue remains lower...than anyone expected a few years ago." After all, the word anyone makes that statement an impossible claim on the face of it. The Congressional Budget Office, in it's August 2002 Budget and Economic Outlook -- written before President Bush's 2003 tax cuts had even been proposed -- expected $2.244 trillion in revenues for fiscal 2005 (the fiscal year just ended in September). In the CBO's latest budget update (October 6), it estimates fiscal 2005 revenues at $2.154 trillion. So if the CBO is "anyone," then yes -- revenues remain lower than expected. But barely -- only by $90 billion, or about 4%.

What's especially interesting about the CBO's analyses, then and now, is that back in 2002 they estimated fiscal 2005 GDP to be $11.936 trillion. In fact, it turned out to be $12.308 trillion -- $372 billion, or 3% higher. So let's put these numbers together. We get $90 billion less than expected in tax revenues. We get $372 billion more than we expected in GDP. Sweet deal, huh? I'd do that trade all day. It's an arbitrage! And what exactly happened in the intervening time between 2002 and 2005 that could have caused that wonderful thing to occur? Yep -- the 2003 tax cuts.

Just in case you missed it:

We get $90 billion less than expected in tax revenues. We get $372 billion more than we expected in GDP. Sweet deal, huh? I'd do that trade all day.

Again please:

We get $90 billion less than expected in tax revenues. We get $372 billion more than we expected in GDP. Sweet deal, huh? I'd do that trade all day.

Don't be trapped by those statist blinders!!

Monday, December 12, 2005

Insightful comments

This gem speaks for itself:

Roberts: The biggest philosophical problem we have today with government is government's desire to micromanage this industry or that one with this tweak or that yank while ignoring the intended or unintended consequences that inevitably follow. Hayek said it best: "The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design." Failing to understand this insight is the problem with the nation's energy policy, telecom policy and health policy just to take a few examples. Fiddling with energy policy is unlikely to make consumers better off. My hope is that the price of gasoline will come down a little bit more and politicians won't feel like they have to show they care about us.

Kudlow: Russ: was that part of Hayek's "fatal conceit"?

Roberts: Yes, Larry, that is what Hayek called the fatal conceit from the book of the same title. The Road to Serfdom is his most famous book. But the deepest insights are in The Fatal Conceit. Unfortunately, it is not light reading. But hey, at least it's short.

This one has some valuable insight into policy and decision making.

Roberts: … There is a virtue in not looking to far ahead and that's that a lot of bad solutions are never implemented. Samuel Johnson said "When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully." There is something to be said for solving problems with a focused mind. When Social Security and Medicare head south, we'll focus on them. And if we don't mess up too badly, we'll have a lot of wealth to use in solving the problem.

Our Grandchildren's Debt Burden in 2050

Over at the Skeptical Optimist Steve Conover is at it again, doing some interesting analysis. After reading a number of very gloomy articles about the debt burden/economy our grandchildren could inherit, he noted:

All scenarios were bad news, and were, of course, our fault for not being “fiscally responsible” today. Some were written by people with economic perspectives I highly respect; others by analysts with skills I highly respect; others by journalists or politicians with economic knowledge that commands little to none of my respect. But the common thread was the terrible scenario that “could” come about.

He then did his own analysis, a sensitivity analysis, and guess what he found:

The key word is “could.” The use of that word in all those articles implied that maybe, just maybe, there might be some other scenarios, not so gloomy, that also “could” come about. So I decided to spend a few evenings testing the possibilities.

Sure enough: It turns out that in many plausible scenarios, the future’s so bright I gotta wear shades.

It’s immediately obvious that productivity growth (input #4), the key driver behind GDP growth, is of overwhelming importance.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Krazy in Kansas?

The critics, in my opinion, are quite right that "intelligent design" is an (apparently successful) attempt to inject creationism into Kansas public schools. I'm less convinced that the mere mention of the possibility of a superempirical design force, without filling in any of the details, violates the constitutional separation of church and state. I think, at worst, it is possibly a step onto a slippery slope that pushes towards violating the separation of church and Kansas. I don't think you're going to find California schools rushing to teach intelligent design.The 6-4 vote was a victory for "intelligent design" advocates who helped draft the standards. Intelligent design holds that the universe is so complex that it must have been created by a higher power.

Critics of the new language charged that it was an attempt to inject God and creationism into public schools in violation of the separation of church and state.

Supporters of the new standards said they will promote academic freedom. "It gets rid of a lot of dogma that's being taught in the classroom today," said board member John Bacon.

And the supporters have a good point. It's not that allowing the teaching of intelligent design will "get rid of a lot of dogma", but it does allow balancing dogma regarding evolution with creationist dogma. I'm absolutely convinced at this point that many of the proponents of evolution are "True Believers". They use terms like "believe in" when talking about evolution, common descent, etc., which clearly implies a religious or dogmatic belief. If you don't believe that, consider the following:

It is absolutely safe to say that, if you meet somebody who claims not to believe in evolution, that person is ignorant, stupid or insane (or wicked, but I'd rather not consider that). -- Richard Dawkins, a leading proponent of evolution, (September, 2001)Dawkins later defended this statement, so it wasn't just a slip of his tongue. The statement wraps up a definition of dogma with the definition of what is heretical thought with respect to the dogma. If that's not the speech of a believer, I don't know what is.

In addition, the board rewrote the definition of science, so that it is no longer limited to the search for natural explanations of phenomena.

Many opponents point to this "redefinition" of science as one reason not to teach Intelligent Design. I don't think this holds much water. The first definition for science is "The observation, identification, description, experimental investigation, and theoretical explanation of phenomena." It doesn't say that it need be limited to the search for natural explanations. The other approach to eliminating the "redefinition" of science is to call it "Science and Philosophy of Science" class. There's no reason such topics need to be taught at different times. I personally think an emergent and integrated curriculum is a better approach anyway.

The article states that the Kansas School Board is "[r]isking the kind of nationwide ridicule it faced six years ago" when it contemplated the same thing. Unfortunately, it may be that evolution proponents' position in this debate is so weak, that the only weapon they have left is to ridicule the other side.

Thursday, December 08, 2005

The Big Plan

Over at Cafe Hayek Don Boudreaux holds forth on journalist David Ignatius' fascination with Amory Lovins idea for a grand plan to solve our problems, energy related and otherwise.

The political appeal of The Plan is equivalent to the sex appeal of Salma Hayek. The political appeal of the market is equivalent to the sex appeal of Kermit the Frog.

Lovins has Ignatius convinced:

Lovins's plan is precisely the sort of thing a great nation should explore as its biggest manufacturer is skidding off the road. The details are complicated, but the essence is pretty simple: Lovins argues that by radically transforming the materials used in cars, trucks, airplanes, office buildings and factories -- substituting carbon-fiber composites and other lightweight products -- the United States could cut its oil use by 29 percent in 2025 and an additional 23 percent soon thereafter.

This "national mission," of course, involves taxes as well as government loan guarantees and other subsidies aimed at fundamentally changing the materials out of which automobiles and buildings are built – a change that, because it requires new technologies, will also energize U.S. innovativeness.

But it’s late, so I’ll just point you to Ignatius’s closing paragraph:

I'm no technologist, so I can't evaluate the technical details of Lovins's proposal. What I like is that it's big, bold and visionary. It would shake an America that is sitting on its duff as foreign competitors clobber our industrial giants, and it would send a new message: Get moving, start innovating, turn this ship around before it really hits the rocks.

This paragraph reflects an attitude that is rich soil for totalitarianism to take root. It ignores individual freedom; it ignores the possibility that the admired Big Plan might be flawed, either technologically or economically or both. Ignatius is all orgasmic simply because The Plan is centralized and Big and (allegedly) will compel or inspire the masses once again to behave in ways that promote national greatness.

Heaven help us.

The real gems in rebuttal are these two comments to the post:

The claim that oil is finite is based on a rather narrow viewpoint. What needs to be taken into account is what the mind can create literally out of thin air. A natural resource isn't valuable until innovative and enterprising minds see the potential. Therefore, if I manage to invent a chemical process that doubles the efficiency of every single combustion engine in the world, have I not essentially doubled the amount of oil in the world? Likewise, if I manage to invent a new building procedure that uses half the wood without any sacrifice in strength, have I not essentially doubled the amount of lumber in the world?

This is why simply looking at oil as a finite physical resource is narrow. One needs to also take into account how usage is changed as a result of prices. Increases in price encourage better frugality.

What Ignatius is missing is how woefully ignorant is 'The Plan'. It relies on the knowledge of a mere handful of people.

The market on the other hand uses the knowledge of the millions of participants. Which is why decentralized decision making systems outperform central planning, and always will.

Statism, opiate of the elites!!

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

Nationalized Health Care

However, it doesn't necessarily matter all that much if you raise taxes for socialized medicine or employers cut wages. Even if you tax other "rich" people, the economic opportunity lost by redirecting those funds from investment to healthcare services will depress wages over the long haul. I recently described one of many mechanisms for how taxation reduces the economic well being of the less well off here. Also, it's no coincidence that most countries with lavish healthcare supplied by the state are not doing so hot economically.

That being said, I actually favor a variant on a nationwide health insurance approach. I think that everybody should be covered by the federal government for catastrophic and some preventative care. The preventative care portion is admittedly extremely difficult to define and I don't have the time to elaborate those details now. However, the catastrophic portion is more straightforward. The government insures everyone beyond some individual out of pocket expense for a given year. That limit would need to be set moderately high, perhaps something like $2,500, maybe lower, maybe higher, maybe means tested, I'm not sure. Perhaps the schedule of services covered would exclude certain procedures (the old liver transplants for alcoholics dilemma). Everything else is simply out of pocket expense.

In addition, I'd eliminate the tax deduction for employer funded health insurance. Why? Because the poor pay very little in taxes so it wouldn't affect them much while the better off pay more in taxes - but they can afford to do so.

These sets of actions would push the health care sector to be more market driven. High tech market driven areas tend to reduce cost and price very quickly. Consider cell phones, Internet, digital cameras, television, etc. Health care may respond similarly. If so, then we'll all get better healthcare at lower cost.

Taxation part I

Fill in the blank: "Tax cuts for the ______."

This is posed by Steve Conover...Like Pavlov's dog, we've been successfully trained by our politicians how to fill in that blank. It requires no thought; it's a reflex. It fits on a bumper sticker, it evokes powerful emotions…

“Tax cuts for the rich” is the politically correct answer. It's part of our culture. For example, it only takes Google a scant two tenths of a second to find 307,000 instances of that phrase on the web.

However, I am personally far more interested in the economically correct answer, as opposed to the politically correct one. I’ve learned through experience to check the facts, instead of taking our politicians’ rhetoric at face value—

The top one percent of the tax returns yield 35 percent of the IIT revenue, up from 23 percent in 1985. The bottom fifty percent of returns yield 4 percent of the IIT revenue, down from 7 percent in 1985.

At this point, it was starting to look to me as if the rich, especially the super-rich, are shouldering more and more of the income tax burden—and that the bottom 50% of taxpayers are shouldering less and less. [That’s good, isn’t it?]

The super-rich paid 25% of their adjusted gross income to the government. Every other group paid less than 17%. The bottom 50% of taxpayers paid 3% of their AGI. [Is that good, too? Seems to me the hierarchy is just what you’d expect in a progressive taxation system.]

Lastly, it’s obvious that everybody got a tax cut, not just the rich. The bottom 50% paid about half of the portion they were paying before the “tax cuts,” and the top 1% are paying about 90% of the portion they paid before—but every taxpayer, every single taxpayer, got a tax cut. Notice how every line on the chart starts dropping in 2001.

Try asking people how much of the tax burden the top 1% or 5% should pay, ask how much they think these individuals pay - see what kind of answers you get...

Bruce Bartlett covers the related matter here...

A few weeks ago, the Internal Revenue Service released data on tax year 2003. They show that the top 1 percent of taxpayers, ranked by adjusted gross income, paid 34.3 percent of all federal income taxes that year. The top 5 percent paid 54.4 percent, the top 10 percent paid 65.8 percent, and the top quarter of taxpayers paid 83.9 percent.

Not only are these data interesting on their own, but looking at them over time shows that the share of total income taxes paid by the wealthy has risen even as statutory tax rates have fallen sharply. A growing body of international data shows the same trend.

Of course, it would be a mistake to conclude that tax increases will not raise the wealthy's tax share or that tax rate cuts always will. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that the percentage of federal income taxes paid by the top 1 percent of taxpayers almost doubled during a time when the top income tax rate fell by half.

A common liberal retort to these data is that they exclude payroll taxes, which are assumed to be largely paid by the poor. However, it turns out that when one includes payroll taxes in the calculations, it has far less impact on the distribution of the tax burden than most people would assume, because the wealthy also pay a lot of those taxes, too.

At some point, those on the left must decide what really matters to them -- the appearance of soaking the rich by imposing high statutory tax rates that may cause actual tax payments by the wealthy to fall, or lower rates that may bring in more revenue that can pay for government programs to aid the poor? Sadly, the left nearly always votes for appearances over reality, favoring high rates that bring in little revenue even when lower rates would bring in more.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Perfect Storm for the Democrats

George Bush hasAfter chuckling at this I started to think about it seriously. I know it's not meant for serious consideration, but it's just my nature to analyze everything under the sun. It struck me that those eight points are the most common eight points put forth by the Left before the 2004 election to bash Bush and the Republicans. The problem is that even with these claims being constantly bandied about in the media, Bush and the Republicans had a pretty solid victory in 2004.

- started an ill-timed and disastrous war under false pretenses by lying to the American people and to the Congress;

- run a budget surplus into a severe deficit;

- consistently and unconscionably favored the wealthy and corporations over the rights and needs of the general population;

- destroyed trust and confidence in, and good will toward, the United States around the globe;

- ignored global warming to the world's detriment;

- wantonly broken our treaty obligations; he has condoned torture of prisoners;

- attempted to create a theocracy in the United States;

- appointed incompetent cronies to positions of vital national importance.

Would someone please give him a blow job so we can impeach him?

What's worse is that most of those eight points are somewhat less "true" today than they were in 2004 when Bush won and it looks to me like the trend may well continue to favor Bush and the Republicans. Let's consider the points one by one:

- The war seems somewhat less disastrous at this point than it did before the 2004 election. There is a Iraqi constitution, elections are forthcoming, the Iraqi army is getting closer to being ready to take over from us, and Iraqis are generally pretty upbeat. It may still all fall apart, but it could also be that by 2008 it will be difficult to consider Iraq a disaster.

- The budget deficits have been getting smaller every year. By 2008, the federal budget may even be balanced, in which case this won't be an issue that the Democrats can hang their hats on.

- On the surface, this point was and remains true (though the "unconscionably" part is definitely arguable). Indeed, the Republicans' business friendly policies have led to record growth in corporate profits. However, as I've written previously "[w]ages and profits are always linked over the long run. When doing business becomes more profitable, companies seek to expand their business. This increases the demand for labor which reduces the labor pool causing wages to increase. Because of these earnings increases, I expect to see the median family income increase nicely during 2006 and 2007". If I'm right, most people will be feeling richer just in time for the 2008 election season. I don't think all that many middle class people really care about the "wealthy and corporations" as long as they are getting richer too.

- I just got back from Europe and I got the feeling while there that anti-Bush sentiments are subsiding a little. Perhaps they are just growing used to him; perhaps new European leaders such as Germany's new chancellor, Angela Merkel, are causing Europeans to rethink their relationship with America; or perhaps they're just focusing too much on their own troubles of poor economic growth, growing pension and other liabilities, and ethnic unrest to worry about America and Bush so much anymore. At any rate, they seemed less interested in Bush bashing than during my visits earlier this year and last.

- Many other countries are now backing away from meeting greenhouse gas emissions targets (see here, here, and here) which makes it seem like Bush and the Republicans were just more realistic than everybody else.

- Torture in certain conditions is supported by 60% of Americans. That may be horrifying, but it is reality and, as a result, point 6 doesn't help the Democrats all that much, if at all.

- A large majority of Americans want more religion. This makes Bush's religious stance a feature, not a bug, to most Americans. Indeed, the Democrats appear to be unfriendly to religion and this hurts them badly in elections.

- Sure, but what President didn't appoint incompetent cronies? Besides, Bush isn't running again, so his successor can't be faulted ahead of time for appointing incompetent cronies.

Milton Friedman - proponent of individual freedom

...at the top of the totem pole for their contributions to man's progress and to human understanding comes Milton Friedman, and his wife, Rose D. Friedman.

In about 1965, the whole world was worshiping at the altar of John F. Kennedy's words, "Ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country." Professor Friedman, in his writing, said that neither was a fitting question in a free society. People should be asking what they can do for themselves and their friends and communities, not how they can serve the state or what they could get as wards of the state.

This became the beginning of Professor Friedman's 1980 PBS series "Free to Choose," also about the role of individual freedom in creating a prosperous, politically free society. At a time when the prevailing liberal ethos was all about the state, planning and direction from on high, Professor Friedman and his wife stood up for the glory of the rights and choices of the individual. From the individual, not from the state, came creativity, progress, freedom, prosperity. From the state came oppression and stagnation. While (just as a humble opinion) I see the state having a vital role in securing freedom for minorities, defending the society against aggression, and delivering the mail, Professor Friedman's basic point is certainly correct. (He saw major roles for the state in enforcing antitrust laws and insuring banks and in other areas, too.)

THERE are a few really great names in standing up for the individual in a world where the beautiful people always seem to want the state to tell us how to live - William F. Buckley; Robert L. Bartley, the late editor of the Wall Street Journal's editorial page; and Mr. Reagan - but they all pale before the brain power and ingenuity of Milton and Rose Friedman. If we have a free society today, if we have avoided anything close to another Great Depression, if we have prosperity and fairly stable prices, we owe much of it to Milton Friedman. If we have a free market economy that will yet pull us through our many travails and will be the beacon of hope to the whole world, if we still have a majority of the economy not in the hands of the state, much of the credit goes to Milton Friedman.

I've written elsewhere about the political disease of statism. This was one manifestation of the methodological flaw that infected the social sciences known as collectivism - part of the abuse of reason. As I recently saw written (wish I could remember where) : "collectivism=slavery; individual freedom=life." Milton Friedman is definitely for life!

Monday, December 05, 2005

Investment Time Constants

Capital investment is one of the reasons a modern advanced economy produces as much as it does. In general, if the level of investment increases, so does the amount produced. However, there is a delay between when a dollar is invested and when returns on that investment, if any, can be expected.

For some investments, returns occur almost immediately and last a long time but are relatively small. For example, if you own a laudramat, the time between when you invest in a new dryer and when it starts generating revenue might be as little as a few days. The revenue likely exceeds operating costs (or you probably wouldn't have bought it in the first place), and the dryer will provide a small return for many years.

Other investments take a long time to begin producing a return. Examples include pharmaceutical development and developing oil fields. These sorts of investments can take the better part of a decade or more before the first revenue begins to trickle in, and many years more before the peak return occurs.

The economic output at any given time due to investment includes returns from recent investments like the dryer at the laudramat, and investments from the more distant past, for example investments in oil fields. The output of the economy at a given time is dependent on prior investments from a wide range of time - from very recent to decades old.

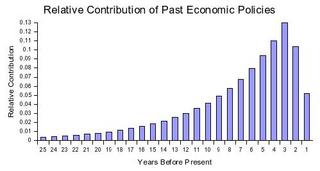

Economic policy can significantly affect investment levels and past investment affects current output. Thus, it follows that the size of GDP can be significantly affected by the accumulated economic policies of the past, with the economic policies from each past year having a different relative contribution. While these relative contributions continuously change and aren't really measurable, I've create the chart below to illustrate what I consider to be a set of plausible relative contributions.

I imagine that the peak year of the economic policy contribution is around two to three years back and then the contribution is smaller and smaller the farther back you go.

It depends though. Some economic policies, mostly bad ones, can have an effect very quickly. Monetary policy that is significantly too loose or too tight is one example. A significant increase in capital gains taxes is another. It's simply much easier to destroy than to create.

Nonetheless, a significant part of the credit or blame for how the economy is doing belongs to past presidents as well as the present one. The credit for the economy in 1999 belongs to not only Clinton but also Reagan. The economy is excellent right now and is the accumulated economic legacy of Reagan, Clinton, and George W. Bush.

Back from The Netherlands

What's interesting about that to me, is that the numbers tell the same story. There has been significantly GDP per capita growth in Europe since the 1970s than here in the United States. And it shows.