In the 1937 essay "Economics and Knowledge," Hayek formulated the "knowledge problem" this way: "How can the combination of fragments of knowledge existing in different minds bring about results which, if they were to be brought about deliberately, would require a knowledge on the part of the directing mind which no single person can possess?" Hayek's answer was that market institutions manage to gather the "fragments of knowledge" and coordinate individuals toward efficient outcomes. No one knows just what combination of production inputs will minimize costs and produce the quantity of goods that satisfies demand. But the operations of the market, in which prices are not fixed but respond to changes in supply and demand, are a "discovery procedure" (as Hayek would later put it) for such information.This discovery process gives us a means of coping with ignorance and uncertainty.

Lest that sound like a small insight — the stuff of an introductory economics textbook — note how Hayek's answer diverges from standard neoclassical economic theory. In the textbook version, individuals are assumed to have perfect rationality and foresight. They then unfailingly make decisions about the allocation of their resources that maximize their utility. While this model no doubt has its uses, its unrealistic assumptions are often seized upon to discredit laissez-faire economics.The nearly obsessive focus on mathematical models in economics may have past a peak, but the positivist bent still remains.

Hayek, like many of his peers (and the Austrians in particular), was also inclined toward skepticism of the elusive, perfectly rational homo economicus. But rather than take the apparent implausibility of the standard model as a reason to reject free markets, Hayek saw that free markets helped compensate for the limitations of human knowledge and rationality. By spontaneously gathering dispersed information and coordinating it through the setting of prices, markets make the choices of individual men both better informed and more rational than they would otherwise be. Hayek also understood — long before most, and to his great credit — that the incompleteness of any individual's knowledge makes central economic planning both impossible and undesirable. (Undesirable in that the planner must, as Hayek explained in the 1939 pamphlet "Freedom and the Economic System," "impose upon the people the detailed code of values that is lacking" — paving a path toward despotism.)

Caldwell goes on to show how Hayek's reflection on the knowledge problem led him to conclusions about the methodology of economics. Just as no central planner knows enough to bring about an efficient economic outcome, no economist knows enough to make precise forecasts. Instead, economists must content themselves with offering general explanations of the principles by which economic outcomes arise, and making predictions about the pattern of future events (rather than predicting specific outcomes). This skepticism continues to rub economists of a positivist persuasion — which is to say nearly the entire field — the wrong way.

According to Caldwell, Hayek's main message concerned "the limits that we face as analysts of social phenomena." In this vein, Caldwell ends with a plea for a renewed interest in the study of economic history — a field that has been almost entirely displaced by economists' ever-increasing interest in mathematical models and empirical analysis. The positivist hope has been that such work would establish law-like relations between events and economic outcomes; but for Hayek — and, as is clear by the end of the book, for Caldwell too — such ambitions smack of hubris.As a further reminder of what we're up against there is this reminder from Marty Fridson.

None of which is to say that empirical work should be abandoned. Hayek's call is for modesty in the profession's aims, not for complete asceticism. But one doesn't have to be an economist — or a political philosopher, or a cognitive psychologist, or anything else — to reflect on the last century and see the catastrophes to which overly sanguine economic planners can lead. For this reason alone, Hayek's challenge is worth remembering, and Bruce Caldwell has done a great service by reminding us of it.

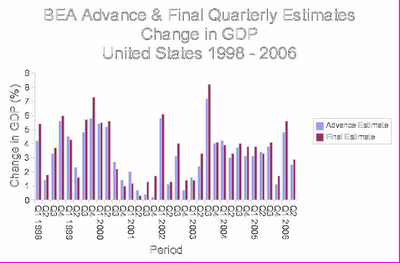

Whether or not seers have insight into future conditions is a testable proposition. If it turns out that they don't, governmental attempts to guide the economy also come into question. Such efforts, after all, rely on forecasts generated by the same methodology that private-sector economists utilize.

The imprecision of economic forecasts isn't a comment on the forecasters' intelligence or work ethic. Rather, it demonstrates that the economy is too complex a system to be adequately captured by existing modeling techniques. The rational response to this realization is a combination of caution and humility.

We can debate and discuss ideas but in the world of policy it's usually best to proceed incrementally and on a contingent basis.