Let's start with a specific definition for Free Trade found by typing "Free Trade Definition" into Google:

free trade noun

noun: free trade; modifier noun: free-trade

1. international trade left to its natural course without tariffs, quotas, or other restrictions.I'll focus on tariffs because that's my preferred way of "restricting" trade. A tariff is just a tax. Taxes are required for governments to operate. Even radical libertarians think that at least a minimal government is required for civilization to flourish and therefore, taxes of some sort (or multiple sorts) need to be collected from somewhere.

I've yet to see a good argument why the tariff sort of tax is less legitimate than any other sort of tax such as the sales tax, income tax, real estate tax, estate tax, capital gains tax, health tax, etc. To the extent that revenues from tariffs can replace those other taxes, I don't think that tariffs are any more onerous for an economy and society than any of those other taxes. In addition, tariffs are a fairly efficient tax in that there are a limited number of ports where goods can enter the country, as opposed to income tax where 300,000,000 individuals in the United States alone have to file.

Trade enables specialization. Specialization leads to efficiency and innovation and enhanced wealth creation, leaving the trading entities better off overall, potentially far better off.

But I think that the incremental advantages of trade diminish as the scale increases. Two people trading with each other are much better off than each doing everything for himself, 100 people better off than 2, a million better off than 100, etc., but it may break down at some point. 500 million may be better off trading with each other compared to restricting trade within groups of 50 million, or maybe not.

How about 5 billion versus a half a billion?

My guess is no.

Consider the approximately half billion people in the North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA). It contains labor from first and third world countries, at least some of nearly all natural resources required for any economy, and extensive diversity of people and geography. I think that NAFTA and the trade that occurs within it is a good thing and very beneficial for the countries that are members.

But I think that if we expand beyond NAFTA, the adverse effects of the chaotic nature of trade will begin to overwhelm the benefits of specialization and economies of scale provided by trade. As a result, I think that NAFTA should impose across-the-board, uniform tariffs on all goods coming into it and that the Eurozone and other free-trade areas should do the same.

A description of the chaotic nature of markets is provided by Professor David Ruelle in his book Chance and Chaos:

The system is perfect stable for r < 3, enabling a false sense of security and ability to predict the system response for other values. By r = 3.6, the system has become completely unstable and unpredictable with rapid further increases in instability as r increases from there.

There are many real-world physical examples of this such as turbulent versus laminar flow of a fluid in a pipe where linear increases of pump pressure lead to more-or-less linear increases in flow rate until a certain flow rate is hit, after which the flow becomes turbulent and massive increases in pump pressure give little or no increase in flow rate. Eventually the pipe will burst from the pressure.

In the economy, chaotic effects are manifested in things like shifting comparative advantages between regions leading to the collapse of whole industries and sub-economies. Examples include: steel shifting to Asia, gutting the U.S. steel industry and leaving the badly damaged rust-belt in its wake; and accelerated devastation of Appalachia from the changing economic viability of coal and farming. Each of these examples were exacerbated by rent-seeking unions, government and environmental regulations, less than optimal management, technological innovation, and foreign subsidies, but the chaotic nature of markets still played a significant role and these other factors are an inherent part of the chaotic global political economy.

As the chaotic effects increase, investment risk also increases. It's easier to get investment for a venture that can provide a positive ROI and an exit strategy in a short time frame than for ventures that have a longer time horizon. This is partly inherent in the risk assessment and its effect on the subjective discount rate used in Net Present Value calculations which penalize longer time horizons. However, a substantial part of the risk analysis takes the chaotic nature of markets into account.

I have personally experienced this sort of effect. I may have a high degree of confidence that I'm the only one working on a certain innovation in a given region, but I'm unable to predict the status of this innovation world wide. Investors, however, want to know if there's a chance they'll be blindsided by some competing group in India, or Israel, or Ireland, or Italy, etc. and if so, will be far less likely to invest. I think that part of slowing of worldwide investment is partly due to this sort of phenomenon. There's a lot money sitting, doing nothing, with nobody willing to pull the trigger to invest that money, because that money will be wasted if competing entities are working on the same thing.

Resilience is affected by chaos as well. In March 2011, an earthquake and tsunami damaged a portion of the northeast coast of Japan and this affected the global supply of motor vehicle parts:

Trade and fluid flows have similarities. When fluid flows become turbulent, backing off the pressure helps. In a more complex fluid system, adding baffles can help. Tariffs are essentially baffles in this context. A 20% across the board tariff would enable redundant manufacturing of various products in different and independent regions, reducing chaos, increasing resilience. While possibly somewhat less efficient, if the manufacturing is shut down in one region due to an earthquake, tsunami, meteor strike, political unrest, invasion, war, etc., the impact on the rest of the world economy will be mitigated.

In summary, I think there are issues of scale when it comes to free trade. I see no reason why tariffs are any more onerous than other types of taxes, and the chaotic and fragility effects are reasons to use across the board tariffs to restrict international trade.

Consider the approximately half billion people in the North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA). It contains labor from first and third world countries, at least some of nearly all natural resources required for any economy, and extensive diversity of people and geography. I think that NAFTA and the trade that occurs within it is a good thing and very beneficial for the countries that are members.

But I think that if we expand beyond NAFTA, the adverse effects of the chaotic nature of trade will begin to overwhelm the benefits of specialization and economies of scale provided by trade. As a result, I think that NAFTA should impose across-the-board, uniform tariffs on all goods coming into it and that the Eurozone and other free-trade areas should do the same.

A description of the chaotic nature of markets is provided by Professor David Ruelle in his book Chance and Chaos:

A standard piece of economics wisdom is that suppressing economic barriers and establishing a free market makes everybody better off. Suppose that country A and country B both produce toothbrushes and toothpaste for local use. Suppose also that the climate of country A allows toothbrushes to be grown and harvested more profitably than in country B, but that country B has rich mines of excellent toothpaste. Then, if a free market is established, country A will produce cheap toothbrushes, and country B cheap toothpaste, which they will sell to each other for everybody's benefit. More generally, the economists show (under certain assumptions) that a free market economy will provide the producers of various commodities with an equilibrium that will somehow optimize their well-being. But, as we have seen, the complicated system obtained by coupling together various local economies is not unlikely to have a complicated, chaotic time evolution rather than settling down to a convenient equilibrium. (Technically, the economists allow an equilibrium to be a time-dependent state, but not to have an unpredictable future.) Coming back to countries A and B, we see that linking their economies together, and with those of countries C, D, etc., may produce wild economic oscillations that will damage the toothbrush and toothpaste industry. And thus be responsible for countless cavities. Among many other things, therefore, chaos also contributes to the headache of economists.

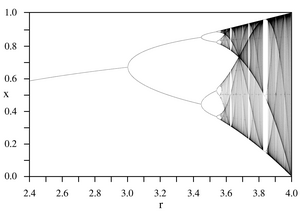

Let me state things somewhat more brutally. Textbooks of economics are largely concerned with equilibrium situations between economic agents with perfect foresight. The textbooks may give you the impression that the role of the legislators and government officials is to find and implement an equilibrium that is particularly favorable for the community. The examples of chaos in physics teach us, however, that certain dynamical situations do not produce equilibrium but rather a chaotic, unpredictable time evolution. Legislators and government officials are thus faced with the possibility that their decisions, intended to produce a better equilibrium, will in fact lead to wild and unpredictable fluctuations, with possibly quite disastrous effects. The complexity of today's economics encourages such chaotic behavior, and our theoretical understanding in this domain remains very limited.A graphical example of "tipping" points in a chaotic system is shown by the bifurcations in the following graph:

The system is perfect stable for r < 3, enabling a false sense of security and ability to predict the system response for other values. By r = 3.6, the system has become completely unstable and unpredictable with rapid further increases in instability as r increases from there.

There are many real-world physical examples of this such as turbulent versus laminar flow of a fluid in a pipe where linear increases of pump pressure lead to more-or-less linear increases in flow rate until a certain flow rate is hit, after which the flow becomes turbulent and massive increases in pump pressure give little or no increase in flow rate. Eventually the pipe will burst from the pressure.

In the economy, chaotic effects are manifested in things like shifting comparative advantages between regions leading to the collapse of whole industries and sub-economies. Examples include: steel shifting to Asia, gutting the U.S. steel industry and leaving the badly damaged rust-belt in its wake; and accelerated devastation of Appalachia from the changing economic viability of coal and farming. Each of these examples were exacerbated by rent-seeking unions, government and environmental regulations, less than optimal management, technological innovation, and foreign subsidies, but the chaotic nature of markets still played a significant role and these other factors are an inherent part of the chaotic global political economy.

As the chaotic effects increase, investment risk also increases. It's easier to get investment for a venture that can provide a positive ROI and an exit strategy in a short time frame than for ventures that have a longer time horizon. This is partly inherent in the risk assessment and its effect on the subjective discount rate used in Net Present Value calculations which penalize longer time horizons. However, a substantial part of the risk analysis takes the chaotic nature of markets into account.

I have personally experienced this sort of effect. I may have a high degree of confidence that I'm the only one working on a certain innovation in a given region, but I'm unable to predict the status of this innovation world wide. Investors, however, want to know if there's a chance they'll be blindsided by some competing group in India, or Israel, or Ireland, or Italy, etc. and if so, will be far less likely to invest. I think that part of slowing of worldwide investment is partly due to this sort of phenomenon. There's a lot money sitting, doing nothing, with nobody willing to pull the trigger to invest that money, because that money will be wasted if competing entities are working on the same thing.

Resilience is affected by chaos as well. In March 2011, an earthquake and tsunami damaged a portion of the northeast coast of Japan and this affected the global supply of motor vehicle parts:

Located in the disaster region and adversely affected by these forces are a number of manufacturing facilities which are integral to the global motor vehicle supply chain. They include plants that assemble automobiles and many suppliers which build parts and components for vehicles. Some of the Japanese factories that were forced to close provide parts and chemicals not easily available elsewhere. This is particularly true of automotive electronics, a major producer of which was located near the center of the destruction.While efficiency is increased by global trade, the above example shows that resilience is not. Concentrating manufacturing in one or a handful of facilities to benefit from economies of scale leaves the world economy more vulnerable to natural and man made disasters.

Trade and fluid flows have similarities. When fluid flows become turbulent, backing off the pressure helps. In a more complex fluid system, adding baffles can help. Tariffs are essentially baffles in this context. A 20% across the board tariff would enable redundant manufacturing of various products in different and independent regions, reducing chaos, increasing resilience. While possibly somewhat less efficient, if the manufacturing is shut down in one region due to an earthquake, tsunami, meteor strike, political unrest, invasion, war, etc., the impact on the rest of the world economy will be mitigated.

In summary, I think there are issues of scale when it comes to free trade. I see no reason why tariffs are any more onerous than other types of taxes, and the chaotic and fragility effects are reasons to use across the board tariffs to restrict international trade.

12 comments:

This one is a work in progress and I'll be updating it - especially as y'all comment.

Bret,

I think your example of resilience does not quite fit. There has been a lot of news lately on new Japanese technologies and improvements that resulted from the Tsunami episode. Their industry basically showed themselves quite resilient then.

The world markets also adapted to the (relatively short) period without those products by ordering it from elsewhere or substituting it. So the system was reasonably resilient worldwide, in my opinion, both in space and time.

But I do not think it alters your final message anyway, you gave a reasonable argument for tariffs as a friction-induced stabilizer. Here I'd just add that "across the board" tariffs must be too far from optimal, there are many situtations where you can easily argue for differentiation.

As the devil is in the details, I'd also point out that tariffs have always been the main tool for vested interests. If you fear Keynesianism not for its face value, but for its potential for manipulation, what to say of tariffs then...?

Clovis wrote: ""across the board" tariffs must be too far from optimal, there are many situtations where you can easily argue for differentiation. ... I'd also point out that tariffs have always been the main tool for vested interests."

I think you just answered yourself as to why I'd do across the board tariffs, didn't you? I'm happy to trade off some supposed optimality for reducing access to special interests.

Clovis wrote: "The world markets also adapted to the (relatively short) period without those products by ordering it from elsewhere or substituting it."

First, no, they didn't. Second, we don't have a completely free worldwide trade regime - if we did, we might be even far more vulnerable to disruptions.

Bret,

---

I think you just answered yourself as to why I'd do across the board tariffs, didn't you? I'm happy to trade off some supposed optimality for reducing access to special interests.

---

It is not so simple. Who decides what will be the tariffs value? That decision will already entail special interests.

For some part of the industry, the tariff will be unnecessary and you'll give them extra protection, and extra profits for free at the expense of the consumer.

For other part of the industry, the tariff may be too low and they will be devastated anyway by the Chinese, so there will be whole areas where the stabilizing effect will not exist.

Who decides who gets what?

---

Clovis wrote: "The world markets also adapted to the (relatively short) period without those products by ordering it from elsewhere or substituting it."

[Bret] First, no, they didn't.

---

Well, you aree surely better informed on that than I am, but I would still appreciate some reference.

I did pay attention to the automovite industry in Brazil, who were affected in the first year due to the lack of those special electronics from Japan. I remember a few reports about relocation of orders to China, South Korea, and so on, and subtitution of technology too.

Clovis wrote: "It is not so simple. Who decides what will be the tariffs value?"

An across the board tariff really is pretty simple. Congress votes on it. Special interests may influence it, but as long as it's a single number, doesn't much matter - it becomes a zero-sum game for the special interests.

My influence would be to set the number to maximize revenues, thereby enabling the reduction of other taxes.

Clovis wrote: "For some part of the industry, the tariff will be unnecessary and you'll give them extra protection..."

Perhaps at first. Think about what would happen next assuming a free market.

Clovis wrote: "For other part of the industry, the tariff may be too low and they will be devastated anyway by the Chinese..."

That's worse than the current situation, how? At least we'd collect the tax revenues.

Clovis wrote: "I would still appreciate some reference. ... the automovite industry in Brazil, who were affected in the first year due to the lack of those special electronics from Japan..."

I'll refer you to you, again you answer your own question. :-)

Examples include: steel shifting to Asia, gutting the U.S. steel industry and leaving the badly damaged rust-belt in its wake; and accelerated devastation of Appalachia from the changing economic viability of coal and farming. Each of these examples were exacerbated by rent-seeking unions, government and environmental regulations, less than optimal management, technological innovation, and foreign subsidies …

You left off communism. Had it never taken over China, then it would have been more economically advanced and integrated with the rest of the world. Instead, we've been dealing with the consequences of communism, and its sudden collapse.

That is a pretty major consideration, and outside the scope of free trade (except to the extent that free trade helped bring it about).

While efficiency is increased by global trade, the [earthquake in Japan] shows that resilience is not.

Sounds to me like it shows the opposite. Suppose there was no free trade in cars. Japan would be the only location for the makers of parts for Japanese cars. Without free trade, the earthquake in Japan then creates total disruption in the Japanese car market. And, depending upon how far you want to limit free trade, it also reduces Japan's ability to recover from the earthquake.

As it happened, SFAIK, the global supply of cars was not particularly affected. Japan's auto makers did, but not the rest of the world's.

I think I'm with Clovis on this. The limited anti-free trade argument you make is open to some inherent weaknesses.

Why 20%, instead of 10%?

Imposing an across the board tariff of whatever amount allows domestic producers to raise their costs by the same amount, so that consumers end up paying more for the same thing.

Why are national boundaries the natural shoreline for tariffs? If it is good for the US vs. the rest of the world, then why not California vs. the rest of the US?

Also, it seems to ignore the most disruptive influence of all -- the 12 or more order of magnitude increase in computing power over the last 40 years.

Finally, I'm not sure that reality was as chaotic as the graphic would indicate. In response to globalization, the US economy has followed pretty much one path from a start state to today. It hasn't swung between wildly different states.

"I'm generally for allowing trade to occur between entities with as little interference from government(s) and others as possible."

Very complex. Pump toxins into the air, poisons into the water and soil and allow very little worker rights or child labor laws w/o interference vs. a trading partner that doesn't. Clearly not free or fair, tariffs are in order.

US trade policies enrich the oligarchy and destroy the spirits and souls of the bottom 80%

Obviously.

Because it is soooo much better that a couple hundred million Chinese live in abject poverty.

Hey Skipper wrote: "Without free trade, the earthquake in Japan then creates total disruption in the Japanese car market."

No. Because those car parts would've been available from multiple other sources, just with a moderate tariff.

The reason car parts were available from multiple other sources, despite one of Nature's temper tantrums, is because there were already deeply developed trade networks.

Either moderate tariffs have an effect -- which means those trade networks won't be as broad and deep -- or they don't have any effect, in which case there is no point.

[Fatboy:] Very complex. Pump toxins into the air, poisons into the water and soil and allow very little worker rights or child labor laws w/o interference vs. a trading partner that doesn't. Clearly not free or fair, tariffs are in order.

Funny, the very worst offenders in that regard are countries (USSR, communist China, North Korea, et al) that completely repudiated free trade.

Post a Comment