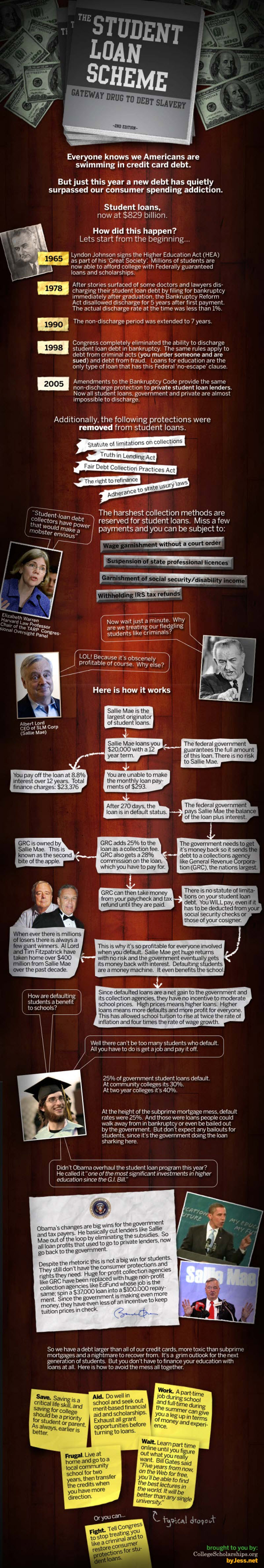

Instapundit has had a number of posts regarding the supposed higher education bubble. However, to me, the most disconcerting part is the massive amount of student loan debt that exists (it exceeds total credit card debt now) and the onerous terms that are attached to that debt as shown by the graphic below.

A whole generation has mortgaged their future (literally). Where are tomorrow's entrepreneurs going to come from if nobody can afford to take risks?

41 comments:

However, to me, the most disconcerting part is the massive amount of student loan debt that exists (it exceeds total credit card debt now) …

Why is that disconcerting? I’ll bet the total amount of car loan debt exceeds credit card debt, too.

But that is a quibble.

I have two kids nearing college age; one is a HS senior, the other a junior. Both are doing well, the senior in particular (7th in a class of 200). She continually gets all sorts of shameless come-hither letters from every elite — and horrendously expensive — college you can name.

She understands — both because she is smart and I told her so — that a college education is an investment, and that her parents are going to pay very close attention to the return. So, instead of, for example, Dartmouth, she is (likely) going to Oregon State.

It is very likely that there is a Higher Ed bubble, and it is there for the same reasons as the real estate bubble: irreconcilable goals.

Ownership and affordability on the one hand, and Credentials and affordability on the other.

Regarding higher education, societally we are not comfortable with the notion that the lack of luck (or sins) of the parents get to circumscribe the prospects of the children. So, the government sets up means to wish the affordability problem away, which, in turn, overheats the higher ed market, until such time as enough people decide they can’t flip the cost of a college degree into sufficiently high earnings.

Inflating the demand also inflates the proxy effect of a college degree. By that I mean that the possession of a college degree is a proxy for qualities that are not specific to the knowledge gained: some level of intelligence and self-discipline primary among them. (Indeed, the proxy effect is largely what keeps the elite college brands going. Someone with a Dartmouth degree on the wall must be smart because only smart people get into Dartmouth in the first place.)

For example, my occupation really doesn’t require a four year degree, but it is nearly impossible to land a job at a major airline without one. Why? Because they feel that there is a significant correlation between having earned a degree and possessing the qualities that are important to avoiding expensive failure.

For most people, and most occupations, something much more akin to a trade school would be far more appropriate; unfortunately, what started as good intentions have created a self-reinforcing cycle of government fueled demand on the one hand, and a self-licking ice cream cone industry on the other.

Skipper, the old adage that a kid should attend the best school he or she can get into still holds true IMO. Learning stuff isn't the most important part of a college education. We had three kids go through within 7 years and it's grind, but you eventually come out on the other end.

Physicians and surgeons have been coming out with enormous debts for a long time, and they have not had difficulty being entrepreneurial, probably because they could easily borrow money.

I know an example, from about 25 years ago, in which a young doctor, who came from quite modest background (she was the first black woman physician licensed in the state), was easily able to borrow $200K to set up a single practice plus another $200K to buy a house, on top of her college debt.

Graduates in, say, chicano studies probably would usually have less trouble.

If employers are demanding meaningless entrance qualifications, that would appear to be another market failure. Employers who recognize they don't need inflated resumes could presumably acquire labor at more attractive rates, padding their profit margins.

I used to work for a woman who followed essentially this strategy. She hired almost exclusively divorced or separated women who had not been in the labor market for a long time.

She got generally competent help at bargain rates, and her workers tended to be loyal, or at least were not constantly leaving for marginal pay increases.

Of course, doing that kind of thing sets you up for violations of various employment regulations. A big (if not the primary) reason for the credentialism in large corporations.

Harry Eagar wrote: "If employers are demanding meaningless entrance qualifications, that would appear to be another market failure."

It's partly true, but part of the market failure is due to government regulation that keeps the cost high of firing an employee.

Having been fired in my time, I can assure you that it didn't cost my former employer a dime -- aside from the dimes he lost by replacing me with a less productive worker.

My former boss might have been subject to a statistical attack based on the fact that she discriminated against married men, but since she paid less than most other employers, who would pursue it?

Harry Eagar wrote: "Having been fired in my time, I can assure you that it didn't cost my former employer a dime..."

Must've been in the days before unemployment insurance (which goes up when you terminate someone), and the increased likelihood of lawsuits due to things like the ADA.

Oh, the poor employers, so afraid of the costs of terminating workers that they had to be forced at gunpoint to export 10 million (or whatever the figure is) jobs to China. My heart aches for them.

But that's exactly the point. Raise the costs of employing people and the jobs will be outsourced.

They, the goverment, can retaliate by regulating/taxing oursourced goods and services to discourage it.

That isn't why the jobs were outsourced, and you know it, because -- as I wrote nearly 30 years ago when Midwestern jobs were being exported en masse to southern states -- 'it won't stop in South Carolina but in South Korea.'

You've probably seen this via Instapundit:

The views that more (formal) education is almost always a good thing and that the loans needed to finance it are “good debt” since it is an investment are both widespread and contribute to the problem. While true to an extent, these views can be and are being carried too far by some, blinding some individuals to the dangers of debt.

The government also shares blame for the high debt load. Part of the problem is that the government seems to be encouraging too many students with little prospect of graduating to borrow money to attend college. . . . But by far the largest share of blame for the tsunami of debt falls on the colleges themselves. As Robert Martin argues, “higher education finance is a black hole that cannot be filled.” Colleges have nonetheless attempted to fill the hole with student borrowing. Such greed, when filtered through a well-functioning market, need not be a cause for concern as the market channels it into useful and productive activities. Unfortunately, the higher education sector cannot be characterized as a well functioning market. The lack of adequate measures of outputs or outcomes is primarily responsible for this, but there are other contributing factors including the non-profit or public status of most institutions, the principal agent problem, and peer effects.

If someone still wants the credential, they might want to minimize the cost.

Circumstances in the world change. Failure to rethink things and adjust accordingly can be problematic.

Harry Eagar wrote: "That isn't why the jobs were outsourced..."

I'm lost. What isn't why the jobs were outsourced? And why were the jobs outsourced?

Bret, good luck getting a straight answer.

They weren't outsourced because the costs imposed by government raised the cost of keeping a worker.

They were outsourced because most employers, though they will not admit it, believe that the Iron Law of Wages is not only just but the only way to run a business. Those who don't believe that have to act as if they do anyway.

American wages were above world levels because, to a great extent, labor was not fungible and the limit to expansion in America has always been labor, not management and only occasionally access to capital.

Globalization, among other things, made many kinds of labor fungible.

Had government done nothing, raised costs or (as actually happened) lowered them, the effect would have been the same, although it is conceivable that the pace would have been somewhat different.

Harry Eagar wrote: "...though they will not admit it..."

The more likely explanation is that they won't admit it because they don't actually believe it. The second likely part of this explanation is that YOU believe in the so-called Iron Law of Wages and are projecting your beliefs onto business owners in which case I'd say it's a darn good thing for workers that you don't own and run a business.

At least you agree that the pace of outsourcing might change.

They don't even all have to believe it. As long as a fair sample do, everybody has to play along.

Both parties used to work to protect America's high standard of living, and even used to praise it in their speeches.

You have not heard a Republican say that since around 1980, for the very good reason that they stopped thinking that way.

Here is a voice of experience.

If employers are demanding meaningless entrance qualifications, that would appear to be another market failure.

This assertion of market failure is a never ending source of mild amusement whenever it arises, because it always takes the form the arguer desires.

The Lilly Bedwetter Act is required because employers are paying more — much more — for male workers than they could pay for females.

Age discrimination laws are required because employers are firing older workers, no matter their greater knowledge and experience, and replacing them with cheaper, younger workers.

And in the space of a para break, employers who were firing expensive workers for cheaper ones are now, blinded by sheepskin, doing just the opposite.

Of course, it just might be that, statistically speaking, the possession of a college degree is correlated with trainability and performance. Obviously a market failure to take that into account.

Oh, the poor employers, so afraid of the costs of terminating workers …

The employees had better be afraid of the costs of terminating workers.

Take a look at long term unemployment rates among countries with strong worker protection laws.

Back in a previous life, I was fired (well, laid off). I eventually landed a decent job. The only reason I got it was because, as a contract worker, I could be released at a moment’s notice. Had the only option been to become a company employee, with all the additional costs that represented, I would have been on the street.

Difficulty of firing always leads to reluctance to hire.

Globalization, among other things, made many kinds of labor fungible.

Absent massive government intrusion in the economy, just how does one stop globalization?

That is entirely aside from whether cost and price might have some connection, no matter how distant.

Harry Eagar wrote: "As long as a fair sample do, everybody has to play along."

Play along with what? That which they won't admit? Because they don't believe it?

How do they play along (with whatever it is)? And why?

From reading between the lines of your comment I might guess that you're trying to say something like, "Some business people believe the fictional Iron Law of Wages is right and just and therefore everybody has to take action to screw their employees wherever possible even if it means damaging their own income and business."

But since that makes no sense, I'm assuming I'm interpreting your comments incorrectly.

I don't see how you stop globalization, Skipper, but it would be nice if people quit praising it without qualification.

It's the old 'Fireproof Hotel' problem, Bret.

Who makes more profit (that is, is more efficient), the guy who spends money to build a hotel that is actually fireproof and charges a premium to travelers to stay there; or the guy who just paints 'Fireproof Hotel' on his wall and charges a premium to stay there?

Occasionally, an example of the second approach will have his hotel burn down and go out of business, but across the broad spectrum of the hotel business, the second approach will attract capital, while the owner following the first approach will be forced out of business.

Now that Harley-Davidson is planning to use part-time workers, who does Harley-Davidson expect will buy its product? Not people who make Harley-Davidson motorcycles, that's for sure.

Harry,

I'm not sure how we got from the Iron Law of Wages being perceived as just by the business community to fraud in advertising of the fire-proofness of hotels, but nobody here thinks that the government should turn a blind eye to making false claims, especially those that put the public at risk.

Nobody thinks the government ought to turn a blind eye to false claims? Why, that would be regulation!

I thought the buyer was supposed to pick and choose in the marketplace, without help.

But the point is, what does the market reward, the true claim or the false claim? If the market is a good thing, then why would government be required to interfere?

Harry Eagar: "Why, that would be regulation!"

Why, yes! Er, sort of.

I know that I posted the opinion of an anarchist recently, but I'm not personally one of them. I believe that the role of government is to enforce a minimum set of "regulations" (laws) that are needed to keep us from directly hurting each other. This would include laws against murder, rape, theft, etc. It also includes contract law such that if two parties enter into a contract and represent that they will do or not do something, they need to follow through.

Thus, if you represent to me that you are renting me a "fire-proof" room in your hotel, then it had better be fireproof.

However, in my opinion, if you represent to me that you are renting me a highly dangerous room that has a high chance of burning me alive, then fine, I can either accept the room, pay for it and stay there, or I can find other accommodations. You however, in my opinion, should have the right to build and offer such rooms. And I should have the right to stay in them if I find the cost/benefit analysis to be subjectively favorable.

So regulations that are acceptable to me just require you to deliver what you claim.

Your preferred level of regulations generally go much further and prohibit certain economic transactions.

I feel that the cost to freedom is too high with your approach.

Bret;

I was an anarchist in my youth but over time came to the same realization you did, which is why I am now a minarchist. I hold out hope that someday we'll advance enough to make anarchism feasible, but we're certainly not there yet.

Susan's Husband,

I was a communist in my youth (mostly thanks to New York State's very left wing public school system). (I was far to the left of Harry Eagar).

Glad to meet you somewhere in the middle-ish. :-)

Darn it Bret. There goes your chance to be elected to public office in California. s/off

Yeah, the voters in California won't elect former Communists.

I've always been a New Dealer, from the time I was indoctrinated by the 'This Is Our Valley' second-grade reader which (although I didn't realize it until later) was pure propaganda for the Rural Electrification Administration.

I'm not opposed to letting businessmen rent out hotels that haven't been fireproofed, so long as it's disclosed. But that was not the point.

The point was, in a competitive market system, it pays to lie about it, and the lie will be richly rewarded.

Kinda like, oh, say, mortgage underwriting. What could possibly go wrong worse than requiring someone to adhere to some minimum standards?

The point was, in every economic system ever invented it pays to lie about it, and the lie will be richly rewarded.

We'd be fine with your skepticism of markets if you were willing to do the same to its alternatives.

Kinda like, oh, say, mortgage underwriting. What could possibly go wrong worse than requiring someone to adhere to some minimum standards?

By requiring them, via the CRA not to adhere to minimum standards.

Harry Eagar wrote: "The point was, in a competitive market system, it pays to lie about it, and the lie will be richly rewarded."

Lying, cheating, stealing, intimidating, etc. are often richly rewarded in many human endeavors. That's one of the reasons those behaviors exist.

Ironically, the competitive market system, especially when coupled with advanced communications such as the Internet, makes such behaviors less richly rewarding than other economic systems. Getting and keeping the trust of the customer is hugely valuable to most companies and they certainly don't want to be caught lying about their products. Surely, you've heard of brand loyalty?

Bret, I first clicked on Amazon.com when my granddaughter was born 13 years ago because I was told they had a large selection of products and were reliable.

Since then I've spent a bundle over there (I have six grandchildren, one of whom lives in France) and in all that time, there hasn't been a single error in an order and neither has there been a single spam to the email address I use there.

Now I first check with Amazon if I want to order anything and rarely order anything from anywhere else.

Brand loyalty has to be won, but once won, will stick.

'Getting and keeping the trust of the customer is hugely valuable to most companies and they certainly don't want to be caught lying about their products.'

I believe Moody's and Fitch and Standard & Poor would not agree with you.

My uncle used to manage the largest cotton spinning mill in the world. He told me JC Penney was his toughest customer, that their standards were the hardest to meet.

The mill went out of business decades ago, and Penney's isn't doing too hot, either.

I do not think that brand loyalty has anything much to do with performance.

And Enron proves that fraud doesn't pay, despite the claims about fireproof hotels.

And Goldman proves it does. Even Enron could have survived a lot longer if its managers had paid attention to what they were doing.

What Enron proves is that dumb crooks generally have shorter careers than smart crooks.

As an aside, economics and business management are like religions in that their adherents routinely embrace concepts that fall apart at the merest inquiry, like brand loyalty.

While it undoubtedly exists as a thing, it falls apart as a concept.

Airlines have spent tens of billions to develop it, without success; and Wal-Mart's success was based on the premise that most shoppers are not loyal to brands, no matter how satisfactory the product or its delivery.

Goldman proves that it takes a government to be a successful thief.

But most people, upon seeing that a method can prove a thing and its opposite, would discard that method as unreliable. You, however, are clearly made of sterner stuff.

Duh?

The brand shoppers (by the gazillion) are loyal to is Walmart.

erp, are you kidding me? If anybody knocks a nickel of Wal-Mart's prices, its stores will empty out overnight.

A few years ago, Bentonville persuaded itself different and spent a lot of money running TV ads purporting to show that Wal-Mart was a valued member of the communities it does business in. That was so ridiculous that it was wound up in short order, and since then Wal-Mart doesn't do anything but advertise lower prices.

You know who else doesn't have brand loyalty? American employers.

Despite their worldwide reputation as the hardest-working and most productive workers, US managers could not wait to ditch them for worse workers.

I have a friend who used to manage plants for Smith-Corona, first in western New York, then in Singapore. He told me that after extensive training, his Singapore workers (mostly farmers from Malaysia originally) could get up to about 80% of the capacity of his New York workers.

Where brand loyalty does exist, it doesn't correlate very well with quality. People can be induced to prefer schlock. In fact, I'd say it's easier to get them to prefer schlock than to prefer good stuff.

Where brand loyalty does exist, it doesn't correlate very well with quality.

Huh?

For almost every significant purchase, I am brand loyal. That is, if the last experience with brand was satisfying, than I am extremely likely to minimize my research costs by continuing to purchase that brand, just as the converse is true.

I am an unashamed Apple fan boy. Why? Everything I buy with that brand is brilliantly designed, works well, lasts a long time, and their customer service is outstanding. That is what builds brand loyalty (NB: Apple is one of the most profitable companies in the world, despite charging many nickels more for the same kind of things than other companies do.)

Recent history proves the point. Detroit, used to a captive market, produced crap. You sell someone a car that has the paint coming off it in a year, and you are very unlikely to sell them another.

People can be induced to prefer schlock.

Ahh, the reflexive elitism of the left.

In fact, I'd say it's easier to get them to prefer schlock than to prefer good stuff.

Right, because you often hear people say, 'I wouldn't shop anywhere but Wal-Mart. It's the service after the sale that brings me back.'

Brand loyalty is like momentum in football. If you don't have it, there's nothing you can do to get it; and if you happen to get it, there's nothing you can do to retain it. It exists, but it's almost entirely random; or perhaps better to say that it is generated by psychological reactions in the buyer that are uncorrelated with what the seller is doing.

Detroit iron is an excellent example to contemplate. There was extreme brand loyalty but it was never closely related to the quality of Detroit cars. Or do you want to propose that there was some real difference between a 1965 Pontiac and a 1965 Buick?

The brand loyalty lasted long after any Detroit cars were worth buying, driven probably by chauvinism as much as anything else.

Nor does competition necessarily hone the sort of quality that supposedly lies behind loyalty to a brand. Before airline deregulation, Delta Airlines enjoyed a high reputation and some (though less) brand loyalty because air travelers were and are highly price elastic.

Since deregulation, Delta has become the airline travelers love to hate. You could argue, perhaps, that Delta management failed to respond competently to competition (no doubt true), but despite some of the worst brand loyalty money can't buy, people still fly Delta and it's one of the biggest airlines.

There's a reason for that, but brand loyalty isn't it.

Where brand loyalty does exist, it doesn't correlate very well with quality.

Except when it does, as the case I provided shows.

Delta is irrelevant, because the product is entirely different. The traveling public has proven time and again it will pay not a dime above the lowest available cost to get from point A to B. Considering they are renting the seat for only a few hours, if that, such a decision isn't irrational.

But to turn around and complain about the lack of amenities is aggravated idiocy in the first degree.

Brand loyalty is like momentum in football. If you don't have it, there's nothing you can do to get it; and if you happen to get it, there's nothing you can do to retain it.

Wrong.

Once again, I refer to Apple. At one time it had great brand loyalty, then the company got rid of Jobs and brought in Scully.

The product became mediocre, and brand loyalty tanked.

Jobs came back, as did outstanding products and customer service.

Now it is one of the highest capitalized companies on the planet, with the kind of foot traffic in its stores that other companies don't have even in their most feverish dreams.

Post a Comment