Dear Don,

I've been following your blog posts regarding free (international) trade for a decade (including the one today titled "Crying Crocodile Tears") and I'm wondering what your thoughts are regarding a number of free trade subtopics. If you had time to blog about them, I'd find that interesting and think some of your other readers would too.

Definition of Free Trade

One thing I've never been quite sure of is your definition of free trade. Here's what I get by typing "Free Trade Definition" into Google[

google]:

free trade noun

noun: free trade; modifier noun: free-trade

1. international trade left to its natural course without tariffs, quotas, or other restrictions.

Is that the definition you have in mind when discussing free trade? The rest of this letter assumes so.

Efficiency of Tariffs

According to the definition above, Free Trade and tariffs (where a tariff is a tax) are mutually exclusive. Yet domestic economic transactions are subjected a huge number and wide variety of taxes such as sales taxes, earned income taxes, real estate taxes, estate taxes, capital gains taxes, corporate taxes, health taxes, transportation taxes, and so forth. It doesn’t appear to me that tariffs are any less legitimate than any of the other myriad types of taxes.

In addition, tariffs are a fairly efficient tax in that there are a limited number of ports where goods worth a great deal can enter the country. Compare this to an income tax where a large percentage of more than 300,000,000 individuals in the United States have to file. I’m under the impression that efficiency is why the tariff was historically used to help keep the kingdom’s coffers complete.

Given that libertarians believe that at least a minarchist government is required and even a minarchist government requires some revenue, to the extent that revenues from tariffs can replace the need for other taxes, I don't see why tariffs are any more onerous for an economy and society than any of those other taxes. To me, tariffs seem at least as legitimate and at least as efficient as of the other forms of taxation.

If a majority of the American people and its resultant bureaucracy prefer tariffs to other forms of tax, is that really so bad from an economic efficiency point of view?

Efficiency Versus Resilience

As a roboticist, I have almost a fetish for electric motors and actuators and the production thereof. While I’ve never visited their factory in China (Hong Kong area), some colleagues that have visited it describe Johnson Electric[johnson] as one of the most awesomely efficient motor production facilities in the world; in one end goes copper ore and other raw materials and out the other end comes millions of motors per day. It’s a shining example of economies of scale and efficiency. Their specialty is automotive electric motors (for power windows, for example) and they produce a significant fraction of all motors worldwide in that niche. If trade restrictions and tariffs were further reduced, no doubt they would have even a larger share of the market and be even more efficient and be able to produce and sell the motors at a somewhat lower cost.

I imagine that part of the appeal of free trade is that there would be many extremely efficient companies like Johnson Electric, each thriving in a specific niche with tremendous volumes, yet with enough competition from a handful of other companies to drive relentless innovation, quality improvement, and cost reduction.

However, there’s potentially a downside to such a scenario. What happens if something happens to Johnson Electric? What happens if there’s political unrest (war), a fire, or a natural disaster?

I find the answer to these questions disconcerting. Examples indicate to me that moderate natural disasters cause significant supply chain disruptions. For example, the 2007 Niigata earthquake [niigata] caused a significant supply chain disruption [farber]:

By now everyone has heard of the M6.8 earthquake up in Niigata last week, a couple of hours north of Tokyo by shinkansen. [...]

One small company in Niigata, Riken (no relation to the research lab with a similar English name, I'm sure) makes 60% of the piston O rings used by *all* of the car manufacturers in Japan. Their plant was badly damaged.

Japan's auto makers, of course, are famed for their "just in time" supply chain management. [...]

Toyota was forced to idle at least 27 plants, Daihatsu four, Honda and other manufacturers several each. Toyota is still shut down, as of this writing (Monday, a week after the quake), and has an output loss of 46,000 cars or more.

A 6.8 magnitude earthquake is not a huge natural disaster, especially not for Japan. In fact, this was merely the warm up for the Tohoku quake four years later which caused the tsunami that in turn caused the well publicized Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster [fukushima]. What was less publicized was that “[l]ocated in the disaster region and adversely affected by these forces are a number of manufacturing facilities which are integral to the global motor vehicle supply chain” [canis] and that “it took three months for Toyota to recover to its pre-earthquake production level.” [matsuo]

You’d think that Toyota would learn to second source most or all of their supply chain and they do for the most part. But even those companies that are using second sources may be fooling themselves. Second sources might possibly mitigate supply chain disruptions if something catastrophic should happen to Johnson Electric, currently supplying approximately 15% of their niche. But if freer international trade enabled Johnson Electric to double their market share of their niche, it would take months for other suppliers to ramp up to cover for the shortfall due to Johnson Electric’s hypothetical absence.

In most dynamic systems, efficiency is in conflict with resilience and robustness. Redundancy leads to resilience and robustness but is antithetical to efficiency. Those economic ecosystems that utilize Johnson Electric are probably quite efficient, but there’s potentially fragility as well.

Is the fragility worth the little bit of extra efficiency? How much extra efficiency is there or would there be if trade restrictions were further reduced?

Scale and Free Trade

Clearly, trade has many benefits and limiting it too much can have serious downsides. As your co-blogger Russ Roberts seems to fond of pointing out, “[s]elf-sufficiency is the road to poverty.” [

roberts]

However, it seems to me that the incremental advantages of trade diminish as the scale increases. Two people trading with each other are much better off than each doing everything for himself, 100 people are better off trading together rather than just 2 at time, a million are better off than 100, etc., but it seems that the incremental gains slow down with each increase in order of magnitude of people trading and it may even break down at some point. Sure, perhaps it's better to have 160 different brands of shampoo rather than the current 80 most popular brands [

brandes], but it doesn't seem like those sorts of advantages are overwhelmingly important.

Consider the approximately half billion people in the North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA). It contains labor from first and third world countries, at least some of nearly all natural resources required for any economy, and extensive diversity of people and geography. I think that NAFTA and the trade that occurs within it is a good thing and very beneficial for the countries that are members.

How beneficial is the additional trade with countries outside of NAFTA for those within NAFTA? Is that even quantifiable?

Chaos and Trade

As we expand beyond NAFTA, I wonder if the adverse effects of the chaotic nature of trade begin to overwhelm the benefits of specialization and economies of scale provided by trade. The chaotic nature seems to me like a waterbed with baffling: without baffling, I jump in and the waves eject my wife onto the floor; yet with baffling, the bed still readily adapts without disturbing my wife's sleep.

A description of the chaotic nature of markets is provided by Professor David Ruelle in his book Chance and Chaos[ruelle]:

A standard piece of economics wisdom is that suppressing economic barriers and establishing a free market makes everybody better off. Suppose that country A and country B both produce toothbrushes and toothpaste for local use. Suppose also that the climate of country A allows toothbrushes to be grown and harvested more profitably than in country B, but that country B has rich mines of excellent toothpaste. Then, if a free market is established, country A will produce cheap toothbrushes, and country B cheap toothpaste, which they will sell to each other for everybody's benefit. More generally, the economists show (under certain assumptions) that a free market economy will provide the producers of various commodities with an equilibrium that will somehow optimize their well-being. But, as we have seen, the complicated system obtained by coupling together various local economies is not unlikely to have a complicated, chaotic time evolution rather than settling down to a convenient equilibrium. (Technically, the economists allow an equilibrium to be a time-dependent state, but not to have an unpredictable future.) Coming back to countries A and B, we see that linking their economies together, and with those of countries C, D, etc., may produce wild economic oscillations that will damage the toothbrush and toothpaste industry. And thus be responsible for countless cavities.

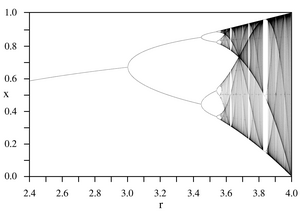

A graphical example of "tipping" points in a chaotic system is shown by the bifurcations in the following graph:

The system is perfect stable for r less than 3, enabling a false sense of security and ability to predict the system response for other values. By r = 3.6, the system has become completely unstable and unpredictable with rapid further increases in instability as r increases from there.

There are many real-world physical examples of this such as turbulent versus laminar flow of a fluid in a pipe where linear increases of pump pressure lead to more-or-less linear increases in flow rate until a certain flow rate is hit, after which the flow becomes turbulent and massive increases in pump pressure give little or no increase in flow rate. Eventually the pipe will burst from the pressure.

What are the effects of chaos and complexity on Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade [kling] as scale increases?

Winners and Losers From Free Trade

In the previous sections I have questioned whether or not free trade is even beneficial in aggregate, especially when considering resilience and mitigating the risk of huge supply chain bottlenecks. There is no doubt that some people are better positioned to take advantage of, or at least weather, the effects of free trade. This subtopic is more political than economic, in fact it's a hugely contentious area in the political arena, but whatever light economics can shed on this would still be helpful.

Because it's such a contentious topic, I could compile a list of a thousand references of various politicians, bureaucrats, and even economists who lament the damage to various groups due to free trade. I'll just list a couple of recent ones.

Charles Murray describes the damage to working class men during the last half century[

murray]:

During the same half-century, American corporations exported millions of manufacturing jobs, which were among the best-paying working-class jobs. They were and are predominantly men’s jobs. In both 1968 and 2015, 70% of manufacturing jobs were held by males.

During the same half-century, the federal government allowed the immigration, legal and illegal, of tens of millions of competitors for the remaining working-class jobs. Apart from agriculture, many of those jobs involve the construction trades or crafts. They too were and are predominantly men’s jobs: 77% in 1968 and 84% in 2015.

A recent paper by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson examines the effect of large changes in trade, focusing on trade with China. Here are some excerpts [

dorn]

“Employment has certainly fallen in U.S. industries more exposed to import competition. But so too has overall employment in the local labor markets in which these industries were concentrated.”

“Without question, a worker’s position in the wage distribution is indicative of her exposure to import competition. In response to a given trade shock, a lower-wage employee experiences larger proportionate reductions in annual and lifetime earnings, a diminished ability to exit a job before an adverse shock hits, and a greater likelihood of exiting the labor market, relative to her higher-wage coworker. Yet the intensity of action along other margins of adjustment means that we will misrepresent the welfare impacts of trade shocks unless we also account for a worker’s local labor market, initial industry of employment, and starting employer.”

“Labor-market adjustment to trade shocks is stunningly slow, with local labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and local unemployment rates remaining elevated for a full decade or more after a shock commences.” While damage to various people in various groups in various regions is not necessarily enough to call for restrictions on free trade, it's also not possible to ignore the political unrest, social ramifications, and potential violence caused by these effects."

There is little more dangerous to a societal order than substantial groups of people who feel that they have little left to lose.

How does one trade of the aggregate economic gains (if any) of free trade with the (alleged) fact that regions and groups have been and will remain devasted? Is any of this quantifiable? In other words, can I know that the likelihood of me losing my job is at least offset by my children being better off due to free trade?

Knowledge and Free Trade

The local knowledge problem is described as follows[

hayek]:

Today it is almost heresy to suggest that scientific knowledge is not the sum of all knowledge. But a little reflection will show that there is beyond question a body of very important but unorganized knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. It is with respect to this that practically every individual has some advantage over all others because he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active coöperation. We need to remember only how much we have to learn in any occupation after we have completed our theoretical training, how big a part of our working life we spend learning particular jobs, and how valuable an asset in all walks of life is knowledge of people, of local conditions, and of special circumstances. To know of and put to use a machine not fully employed, or somebody's skill which could be better utilized, or to be aware of a surplus stock which can be drawn upon during an interruption of supplies, is socially quite as useful as the knowledge of better alternative techniques. And the shipper who earns his living from using otherwise empty or half-filled journeys of tramp-steamers, or the estate agent whose whole knowledge is almost exclusively one of temporary opportunities, or the arbitrageur who gains from local differences of commodity prices, are all performing eminently useful functions based on special knowledge of circumstances of the fleeting moment not known to others.

At least some of the argument about need for dispersed knowledge and action thereon has to do with actual local conditions, the “place” part of “time and place.” When a great deal of production has to do with agricultural, extracting energy from the earth, mining, and even manufacturing to some extent, local knowledge is critical for both efficiency and innovation. For example, I work with lettuce growers, and they plant a different lettuce hybrid seed each week to best match the expected weather conditions for that specific 12-week growing period for that batch of lettuce in that specific field. You can't get much more "time and place" specific than that.

But with much of the United States ecomomy having evolved to services, information, and knowledge, a great deal of the “place” part has been eliminated. Knowledge can move anywhere, often not requiring people to move with it, and often nearly instantaneous.

It often seems to me that this globalization of knowledge has almost turned Hayek's knowledge problem on its head. Instead of having an advantage of local knowledge, no individual or local group is able to have an adequate grasp of the competing activities of everyone else around the world, even in a relatively small niche. As a result, no individual or small group can compete without investment risk that's enormous compared with a few decades ago.

I have personally experienced this sort of effect. I may have a high degree of confidence that I'm the only one working on a certain innovation in robotics in a given region, but I'm unable to predict the status of this innovation world wide. Investors, however, want to know if there's a chance they'll be blindsided by some competing group in India, or Israel, or Ireland, or Italy, etc. and if so, will be far less likely to invest. This is exacerbated by the fact that if I'm even nanosecond later than other groups in filing relevant patents, my investors can be out of millions of dollars with no chance to be able to recover from their losses.

As the chaotic effects due to scale increase, investment risk also increases. It's easier to get investment for a venture that can provide a positive ROI and an exit strategy in a short time frame than for ventures that have a longer time horizon. This is partly inherent in the risk assessment and its effect on the subjective discount rate used in Net Present Value calculations which penalize longer time horizons. However, a substantial part of the risk analysis takes the chaotic nature of markets into account coupled with the limited visibility into global activities.

I think that part of slowing of worldwide investment and your colleague Tyler Cowen's Great Stagnation [

cowen] are partly due to this sort of phenomenon. There's a lot money sitting, doing nothing, with nobody willing to pull the trigger to invest that money, because that money will be wasted if competing entities are working on the same thing. There are a huge and unlimited number of ventures that can be undertaken, but the risk of doing so due to globalization is astronomical relative to a few decades ago.

Might this new version of the knowledge problem be mitigated by reducing free trade?

Simple Alternative to Free Trade

I'm well aware that putting any sort of trade in the hands of governments and bureaucrats is not without substantial risk due to forces explained by Public Choice Theory[

pct] and other factors. Nonetheless, international trade is

already in the hands of governments and I think that simplifying government involvement, yet not completely freeing trade, is potentially a tenable approach.

As a result, I would propose an across the board tariff regime for goods and services coming into NAFTA. I'm not sure what the tariff rate would be and a horde of economists would need to figure that out, but for sake of argument, assume 15%. There would be no other regulations beyond security and military necessity (not allowing importation of nuclear weapons, for example).

This tariff would provide the "baffling" to dampen chaotic behavior of trade. At the same time, any area that truly has a local competitive advantage would still be able to trade with other areas and that would keep trading channels open. Industries would have companies in each of the areas to provide resilience against war and disaster. Knowledge and innovations could still be shared.

Even if none of the benefits above are true, there's not really a large economic downside. The revenue from tariffs would simply offset the revenues from other taxes and those lower other taxes would themselves lead to additional investment and innovation.

Are there other major downsides from an economic perspective? If so, what are those downsides and how big are they?

Summary

There are a number of issues in various subtopics of free trade that leave me far from convinced that global free trade is a great idea. I understand that "But Freedom!!!!" is a reply that you might respond with to any of the questions above regarding free trade, and I'm not unsympathetic to that response, but that is not an economic argument.

The main purpose of this email is to hopefully stimulate you to write about these subtopics on your blog in the future from an economic perspective. I would find it interesting and I think some of your other readers will as well.

Thanks,

Bret

References

[canis] http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41831.pdf

[cowen] http://www.amazon.com/Great-Stagnation-Low-Hanging-Eventually-eSpecial-ebook/dp/B004H0M8QS/ref=sr_1_3?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1461494631&sr=1-3&keywords=tyler+cowen

[dorn] http://www.ddorn.net/papers/Autor-Dorn-Hanson-ChinaShock.pdf

[farber]

http://seclists.org/interesting-people/2007/Jul/123

[fukushima] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fukushima_Daiichi_nuclear_disaster

[google] https://www.google.com/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8#q=free+trade+definition

[hayek] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Local_knowledge_problem

Friedrich A. Hayek, "The Use of Knowledge", American Economic Review. XXXV, No. 4. pp. 519-30 (1945).

[johnson]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnson_Electric

[kling] http://arnoldkling.com/essays/papers/PSSTCap.pdf

[matsuo]

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925527314002278

[niigata] http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2007/07/17/national/powerful-earthquake-slams-niigata

[pct] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_choice

[roberts] http://cafehayek.com/2009/04/gifted-in-nepal.html

[ruelle] http://www.amazon.com/Chance-Chaos-David-Ruelle/dp/0691021007/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1397157389&sr=8-1&keywords=chance+and+chaos+ruelle